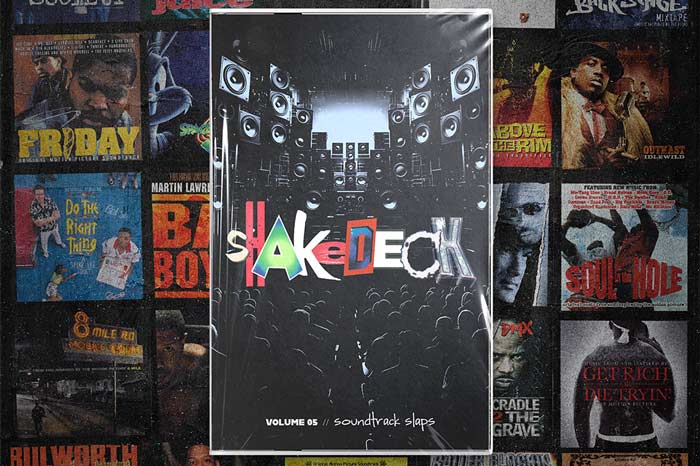

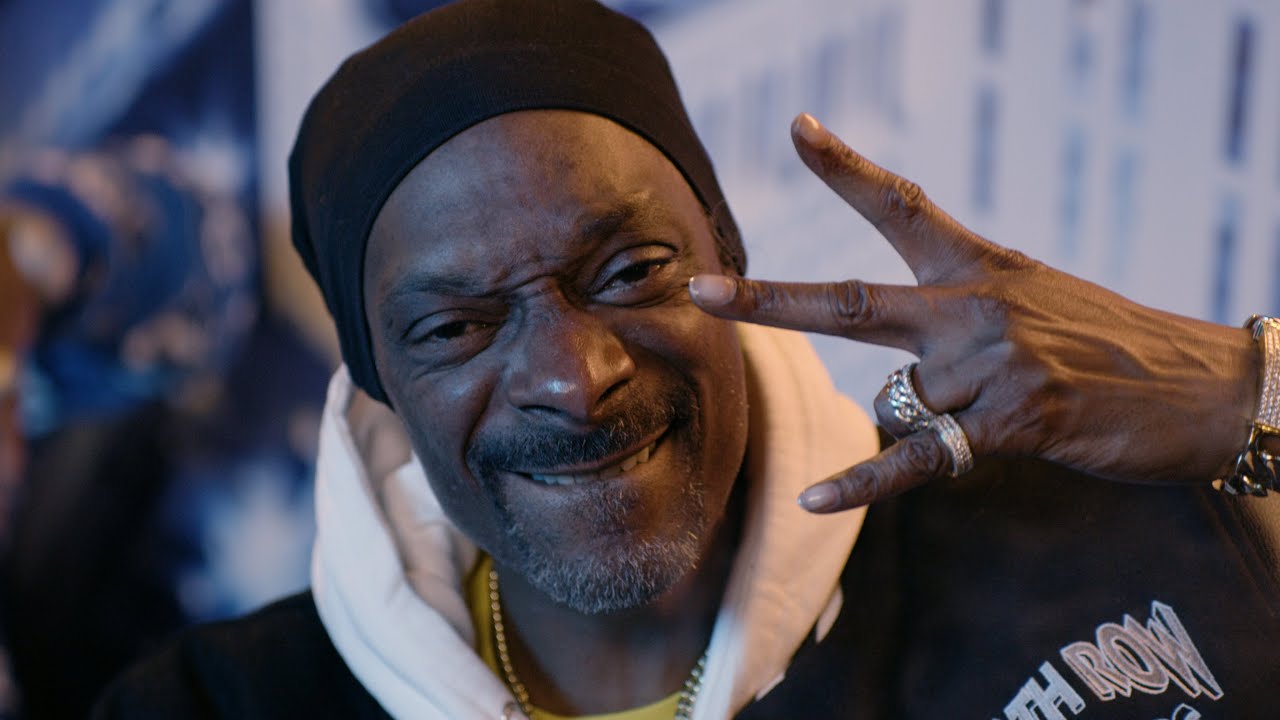

When Doggystyle came out, I was still young enough to have my age measured in months—14, to be exact. My parents brought me home to 230 Handsart Avenue in Winnipeg a short six weeks before “Nuthin’ But A G Thang” hit radio. Redman’s debut had come out four days before I did; in short, I can’t tell you what it was like when Doggystyle showed up on store shelves. I could rattle off numbers (the 800,000 units that put it atop Billboard a mere five years after Los Angeles rap was entirely ignored), or I could point out that before good kid, m.A.A.d. city, before Get Rich Or Die Trying—before even Illmatic—Snoop’s first album was the stop-and-stare debut rap fans were waiting to dissect. But that would be secondhand at best.

Seeing as I wasn’t there, I can’t tell you what Doggystyle meant when it came out. But in the twenty years since then, the Long Beach native has weathered creative and commercial dry spells, lawsuits, bans from entire countries, a famous murder trial, and—perhaps most harrowing—a reality show on E!. The one-time radio juggernaut now sees his celebrity reach far beyond his actual musical audience, a pop culture fixture who only intermittently touches pop radio. Yet somehow, his first LP remains relevant, even vital. It’s a touchstone, a high water mark for a sound it threatened to make a fixture in the mainstream. More than that, Doggystyle is a brilliant personal statement largely misread by critics.

If rap is first and foremost an exercise in charisma, Snoop has always been among its best practitioners. When “Beautiful” and (especially) “Drop It Like It’s Hot” hit, they were undeniably Snoop Dogg songs. And if it seems like I’m damning the tracks with faint praise, it shouldn’t: many great early- and mid-2000s Neptunes productions are of such a singular vision that the credited rapper is little more than an afterthought. The futuristic minimalism on “Hot” made it an instant classic, but Pharrell wasn’t responsible for my friends at Black Hawk Middle School in suburban Minneapolis wearing blue bandanas in gym class. My father, an NHL executive born in 1953 whose music collection begins and ends at an unopened copy of the Beatles’ 1, knows Snoop by name. Years after his last solo hit, he’s still a go-to stand-in for ‘famous rapper’ in jokes and anecdotes.

Now, even the most cynical rap fans would concede that you don’t stay as relevant as Snoop has for two decades without some sort of artistic merit. On the other hand, you could argue that Snoop never dropped a truly essential album after his debut. The records continued to sell for a while, but in hindsight, the No Limit era bleeds into the Geffen years as they wash up on the shores of Jamaica for the ill-fated reggae phase he’s yet to emerge from. So why are lines, flows, and images from Doggystyle so inescapable? The answer could probably be gleaned from just ten seconds listening to his iconic voice: Snoop Dogg rests just a little askew of the boxes in which he’s placed. At first glance, he’s more or less the archetypal West coast gangsta rapper. But upon closer listening, he feels displaced enough to be fascinating, innocent enough for his threats to carry the weight of insecurity and confusion.

There was a lot of youth’s reckless hedonism on the album, but it was always qualified—and not in the way that’s currently en vogue, a la Kendrick Lamar’s “Swimming Pools” or other tracks where rappers openly question their choices. Instead, Doggystyle differs from The Chronic in that Snoop reads as a thoughtful, affected kid molded by his surroundings. Everything down to his soft, malleable delivery suggests nuance that Dre could never dream of (and Ice Cube chose not to employ, even on his most political songs). To be clear, there’s still plenty of debauchery—“Aint No Fun (If The Homies Can’t Have None)” is certifiably depraved. But where most gangsta rap—at least that which penetrated middle America—was an intoxicating fantasy world, Doggystyle has, to this day, the air of real people indulging their vices. That might be the real key to its resonance: Snoop was mean, slick, and dangerous, but he could be your mean, slick, dangerous friend from high school.

Most technical and formal discussions of the album are going to focus on the G-funk sound, but Snoop was remarkably visionary in his sonic approach. In the context of an aesthetic that was brash and larger-than-life, he was unafraid to sound small, nimble, and vulnerable. Rhyme patterns and the mid-bar flow changes are still being replicated today. Beyond that, the lines can still be heard, both in their original form and repurposed in an endless cycle of homage as hooks and opening bars. The execution made an insular album essential listening for hip-hop fans worldwide. Jay Z’s equally narrow debut, Reasonable Doubt, makes use of Snoop’s “dear god, I wonder, can you save me?”, a choice that DJ Premier says was the Brooklyn emcee’s idea. Maybe Snoop’s update on Slick Rick’s “La Di Da Di” [“Lodi Dodi”] was a defiant appropriation of the New York-centric culture that pervaded rap music in 1993, but his cover of the song is housed on an album now stitched immovably into the genre’s fabric.

But all did not go smoothly. Even if the hits were innocuous (if sexist) party jams, the raucous videos became b-roll for the moral hysteria over rap music, Snoop the threat of urban violence perched carefully on his friend’s handlebars. This is obtuse at best: Snoop was never just a cipher for a lifestyle, at least not exactly. In between top-ten hits “Gin & Juice” and “Who Am I (What’s My Name)?” rests “Murder Was The Case”, the album’s chilling centerpiece. The song is a chilling tale of a dying Snoop finding religion as his “body temperature drops”—a pretty macabre narrative considering he was facing basketball numbers for an actual murder charge. If nothing else, the track reminds listeners that there are consequences for all the threats Snoop tosses around on the album, and he couldn’t be more aware of them.

Twenty years after its release, Doggystyle sounds like it came out a week ago. Some find it easy to write off much of Snoop’s output in the years since, but who can blame him? Maybe he’s just waiting for us to catch up.